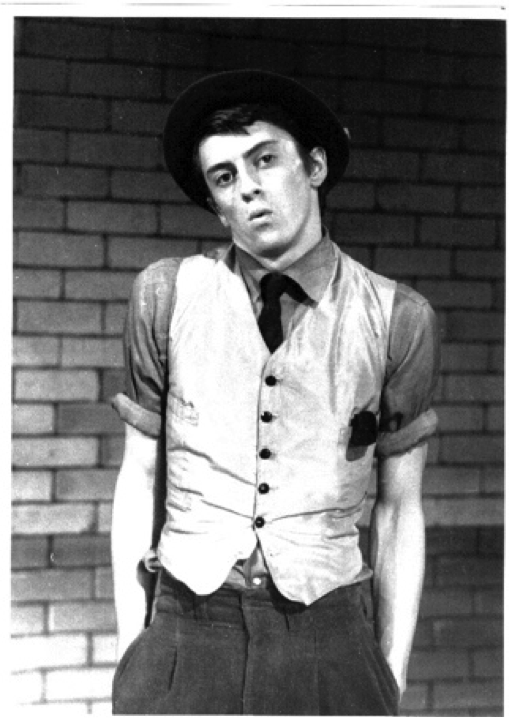

As ‘Snowboy,’ I assumed all I had to do was show up with my lines memorized and give all the other stuff my best shot. I was wrong. Robbins wasn’t interested in ‘best shots.’ He demanded ‘exceptional shots’ of every line, lyric, step, and punch from any dancer who wanted to remain in the room with him. If you didn’t deliver, you were sent out, given time to figure things out, and invited to come back when you thought you were ready. I survived the test more than once. I had to. Otherwise, it wouldn’t take long before outsiders showed up to audition for my role. Snowboy was mine. Snowboy was my role. It was my job to prove it.

As ‘Snowboy,’ I assumed all I had to do was show up with my lines memorized and give all the other stuff my best shot. I was wrong. Robbins wasn’t interested in ‘best shots.’ He demanded ‘exceptional shots’ of every line, lyric, step, and punch from any dancer who wanted to remain in the room with him. If you didn’t deliver, you were sent out, given time to figure things out, and invited to come back when you thought you were ready. I survived the test more than once. I had to. Otherwise, it wouldn’t take long before outsiders showed up to audition for my role. Snowboy was mine. Snowboy was my role. It was my job to prove it.

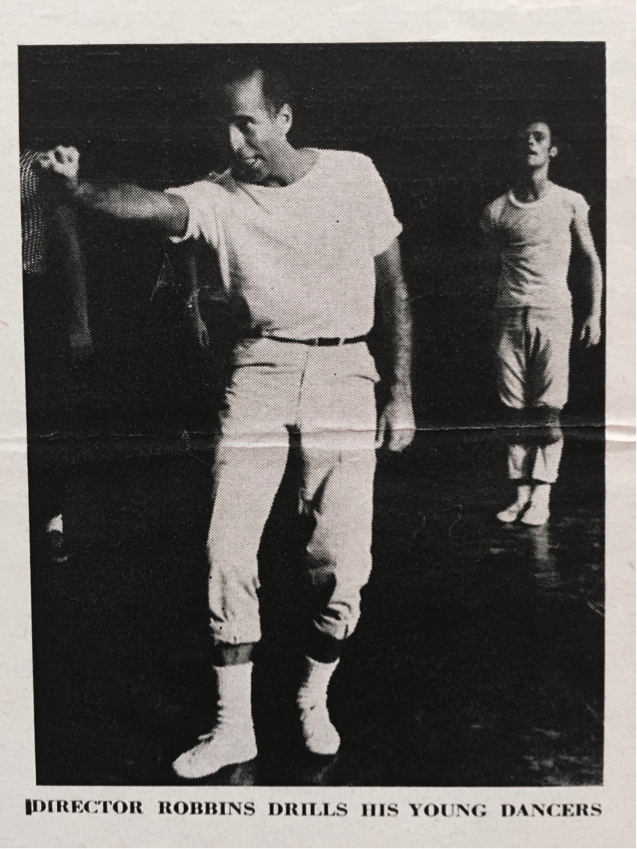

It was clear to everyone who was in control. Robbins decided which of the six versions of ‘Cool’ would end up in the show, which Jet would deliver the strongest punch to a Shark’s gut in the ‘Rumble,’ and which of the 28 deserved onstage moments of their own. Memory retention was the easy part of the job. Competing for bits and pieces was another ballgame.

Did Robbins ever acknowledge any of the 28 for what they gave him? In actual words, no. In a nod, maybe. Seeking ‘approval’ from a genius is pretty futile. Experience taught me that being in the same room should be enough. Do your own validating.

My first shot at validation.

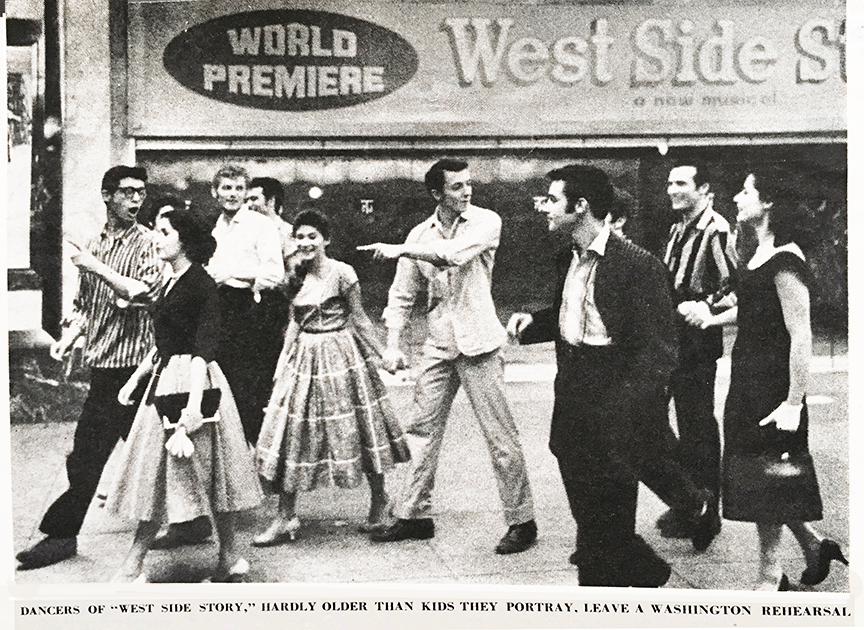

Three weeks into rehearsals, Big Daddy wanted a better shot at seeing the show he was creating. Rehearsals shifted from a dance studio on 56th Street to the bare stage of the Broadway Theatre. Instant adjustment.

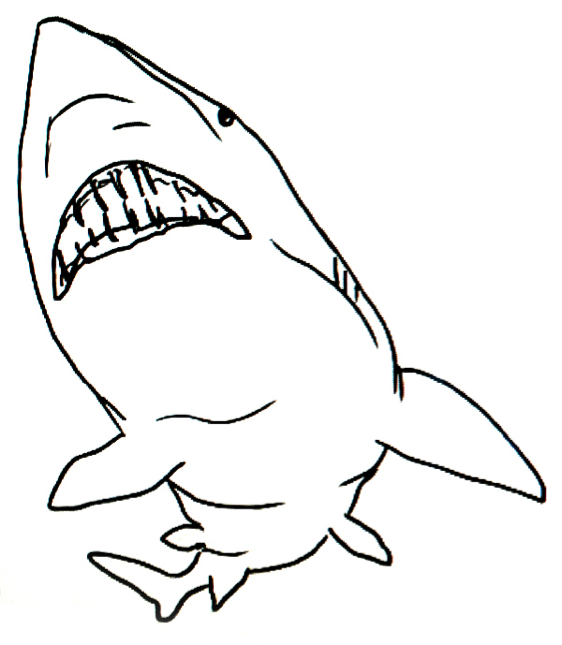

Next morning, I showed up early. At the backstage door, a stack of cardboard in the alleyway caught my attention. Hm. An idea popped in my mind. Do I dare to risk it? I checked my dance bag. Yep, I had a box of crayons. I grabbed the cardboard and ran towards the Jets Dressing Room. In minutes, an image of a nasty-looking shark was underway.

Next morning, I showed up early. At the backstage door, a stack of cardboard in the alleyway caught my attention. Hm. An idea popped in my mind. Do I dare to risk it? I checked my dance bag. Yep, I had a box of crayons. I grabbed the cardboard and ran towards the Jets Dressing Room. In minutes, an image of a nasty-looking shark was underway.

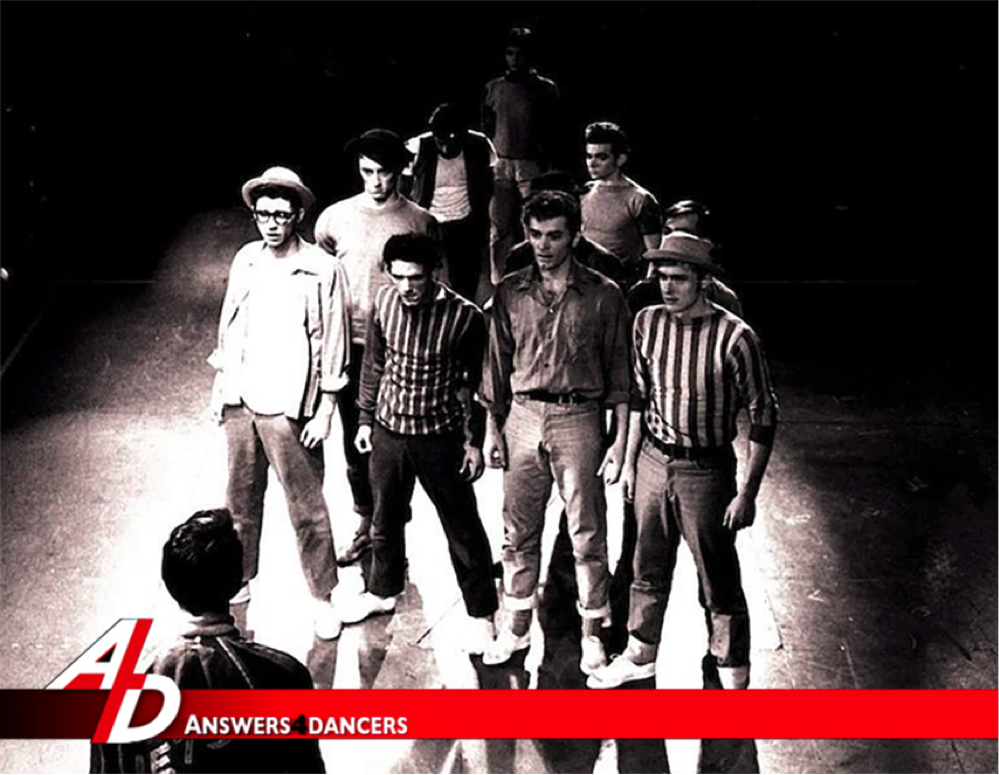

“Whatcha got there, Snowboy?” asked Lee Becker, already in Anybody’s tomboy posture. Other Jets wandered over, and soon a plan to create trouble for the Sharks fell into place.

During lunch break, we quietly climbed the back stairway to the 5th floor with our ‘shark’ in tow. There, spread out in the rafters, we spied on the stage below. Activity on the stage resumed. Robbins checked his watch, and turned to the stage manager, Ruth Mitchell. “Where the hell are the Jets, it’s time to start!’ The Sharks stood nearby, slightly puffed up with postures that said “Well, WE’RE here!’

From the darkness above, voices rang out. “Sharks are dead meat!” we shouted, shoving the huge Shark over the rafters. It was a bullseye; the shark landed right at Robbins’ feet. There was a moment of stunned silence.

We held our breath as all faces turned up. Robbins burst out laughing. This was exactly the competitive spirit he wanted to witness between the Jets and Sharks. As we climbed down from the fly-floor Ruth Mitchell demanded, ‘Which one of you jerks is responsible for this?’ She got no response.

Lee Becker spotted a broken crayon on the floor. ‘Hm,’ she said, picking it up and smiling in my direction… ‘I wonder who this belongs to? For the guy Big Daddy was thinking about firing last week, this crayon might have saved his butt….’ She tosses me the crayon and joins the rehearsal. I fumble and drop it. It rolls over to Big Daddy’s feet. He steps on it.

Looking me in the eye, he winks, and slaps me on the back of the head. I jam the crayon into my pocket and humbly join the rehearsal. I thought to myself. ‘Okay. For one more day, you’re safe. A stupid box of crayons saved your butt.’

If a world-class crash course ever existed in ‘Surviving Broadway Rehearsals,’ 28 dancers were living through it. A few, like myself, started out at the back of the room, but the truth is…each of us traveled a great distance meeting the demands of the showman in charge.

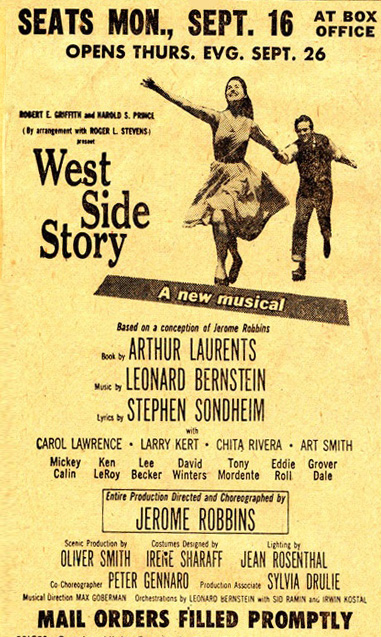

Following the world premiere in Washington DC, the first ad appeared in The New York Times. My jaw dropped. My name was on it. How did in the heck did that happen? With no agent involved, there was no billing clause negotiated on my behalf. The role paid $160 a week. Period. Yet. There at the tail end of ‘featured players’ was my name. Who or what would make that happen? Was it Robbins? Was it luck? Was it a stupid box of crayons?

Following the world premiere in Washington DC, the first ad appeared in The New York Times. My jaw dropped. My name was on it. How did in the heck did that happen? With no agent involved, there was no billing clause negotiated on my behalf. The role paid $160 a week. Period. Yet. There at the tail end of ‘featured players’ was my name. Who or what would make that happen? Was it Robbins? Was it luck? Was it a stupid box of crayons?

Few musicals avoid out-of-town dramatics. West Side Story had its share of them. The most legendary one was a note session in the Walnut Theatre where Robbins backed up and fell into the orchestra pit. Storytellers, over the years, gave it a twist claiming the cast was fully aware of the danger he was in and said nothing. They allowed him to fall. Not true.

Note sessions with Robbins were intense. His eyes nailed you. You didn’t move. You couldn’t look away from him. As he backed away, delivering his demands, none of us saw that he was going to fall into the pit.

BTW: The instant he fell, we all ran to the edge of the stage. He regained his footing. As he climbed onto the stage, he ordered us back into our positions.

Two weeks later following a performance in Philadelphia, Robbins reveals another side of himself. He accepts an invitation to a gathering of the cast. This moment shows Peter Gennaro’s assistant, Wally Seibert, entertains the cast with his imitation of a recent Robbins’ note session. Robbins can be seen seated on the bed behind Chita Rivera.

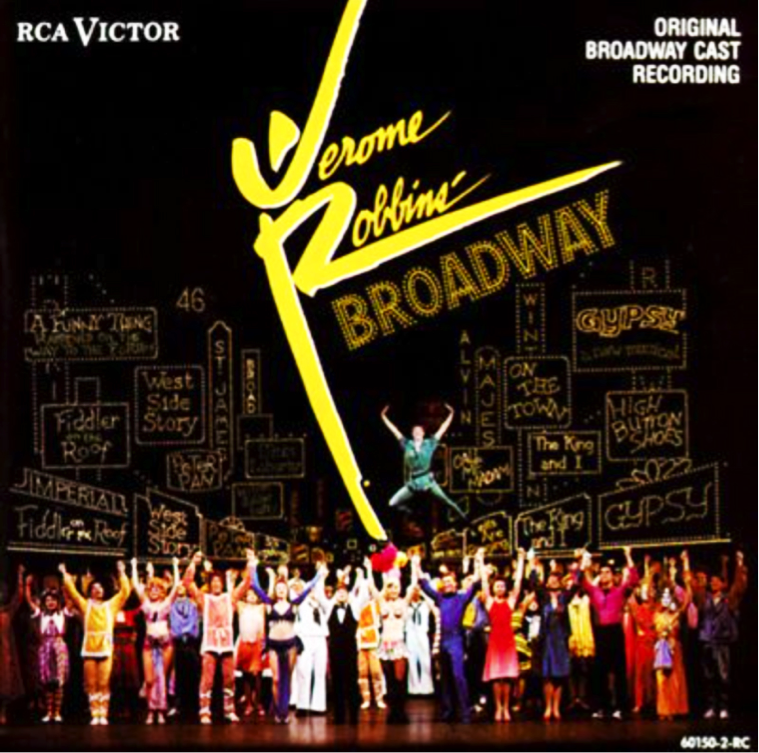

My personal journey with Robbins went on (surprisingly!) for 30 years, culminating when the job of co-directing ‘Jerome Robbins’ Broadway’ was offered during a passionate conversation about the potential Robbins saw in both of us building a new musical out of the eighteen legendary ones he had already created.

CLICK HERE to read the entire story of Direct Bookings / Big Payoffs from the beginning.